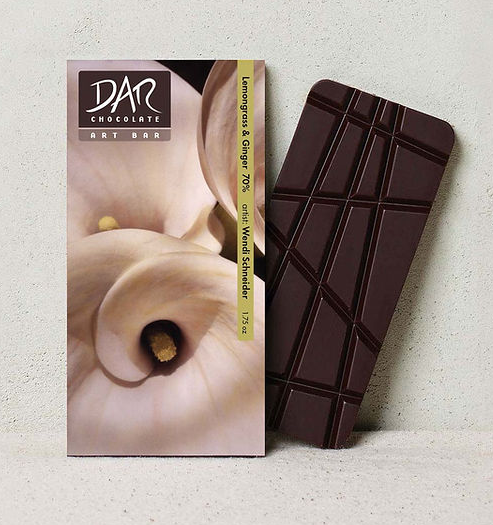

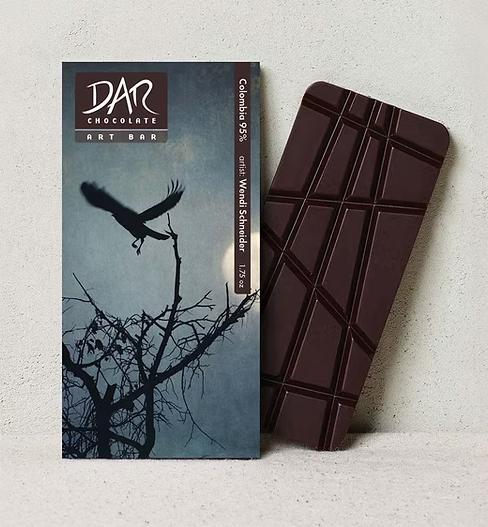

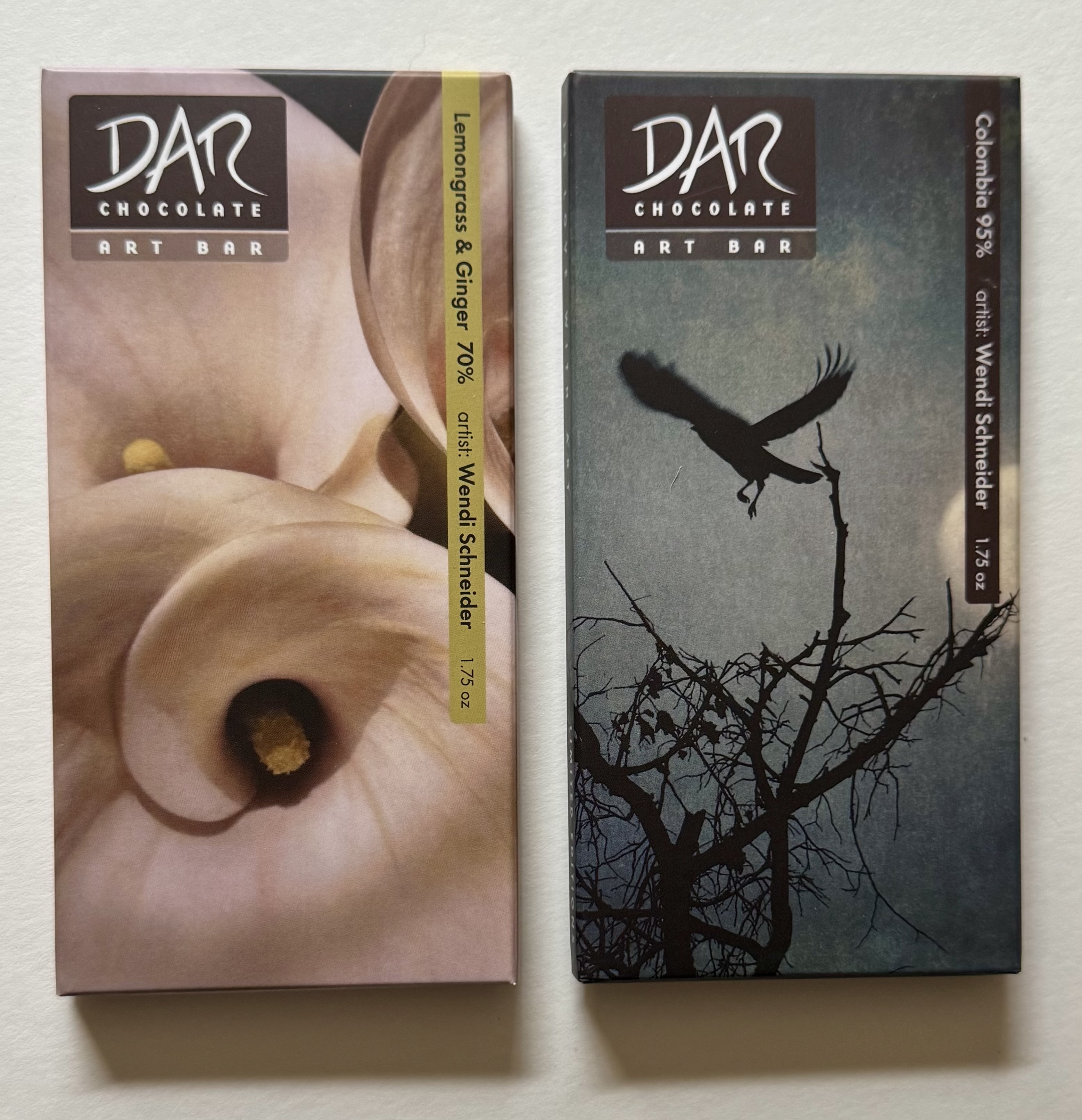

Sweet News! Long time gallery artist Wendi Schneider's work is now featured on chocolate bars! Dar Chocolate Art Bars chose to highlight Wendi's Callas II, 1989 and The Cry of the Lonely Crow, 2019 for Lemongrass & Ginger and Colombia 95% bars respectively. Continue reading for Wendi's musings on her process, and what art and chocolate mean to her.

Callas II, 1989, Lemongrass Ginger 70%

The Cry of the Lonely Crow, 2019, Colombia 95%

Wendi Schneider, Denver, CO, USA

I create illuminated impressions of fleeting moments of grace in the natural world with photography and precious metals. My interest in photography germinated in the early 1980s when using a camera to reference models for my oil paintings. Mesmerized by the possibilities of the photographic art form and the alchemy of the darkroom, yet missing the sensuousness of oils, I began layering oils on my fiber prints to manipulate the boundaries between the real and the imagined. That process laid the foundation for the layering and gilding that later became the 'States of Grace’ series.

What is Art for you?

For me, art is a celebration of all the senses anchored in the visual - an exploration of my spiritual connection to our vulnerable natural world and the transcendence I find in its beauty. My work is testament and tribute, adoration and obligation.

What is chocolate to you?

Savoring dark chocolate is a requisite daily experience of a divine, sensual blend of delectable flavors and antioxidants.

What inspires you, and this piece in particular?

The Cry of the Lonely Crow - Within the “States of Grace’ series are collections that can be curated by subject, theme, or treatment. In 2018, I began a collection called 'Evenings with the Moon.’ In this work, I contemplate the power of universal experiences to unify and find transcendence, engaging the moon as muse. Printed on translucent vellum or kozo and gilded with precious metals, the subjects echo the luminosity of their celestial inspiration.

My images of the night draw on the metaphor of darkness and light to express our shared longing for freedom, peace, love, and harmony amidst the chaos of the world. This synthesis of form and content, paired with poetry and music, encourages the viewer to consider the commonalities in our collective consciousness. We all live under the same moon.

While working on an exhibition in early 2019, I realized I didn’t have an image of a bird with the moon. Setting that intention, I walked towards the corner of our block at dusk - the crow appeared and I captured this image, which was then layered with color, texture, and white gold leaf.

Callas II - The iconic images of Georgia O’Keeffe.

Please contact us at gallery@catherinecouturier.com with inquiries or to purchase the prints.

Wendi Schneider, Callas II, 1989

Wendi Schneider, The Cry of the Lonely Crow, Denver, CO, 2019