Home » Blog

American Photography: Unforgettable Images of the Beauty and Brutality of a Nation

Posted on Feb 14, 2025

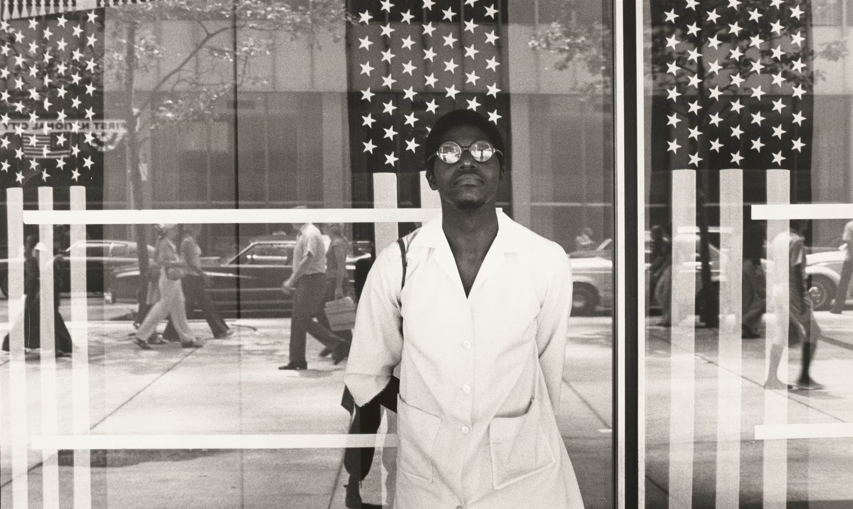

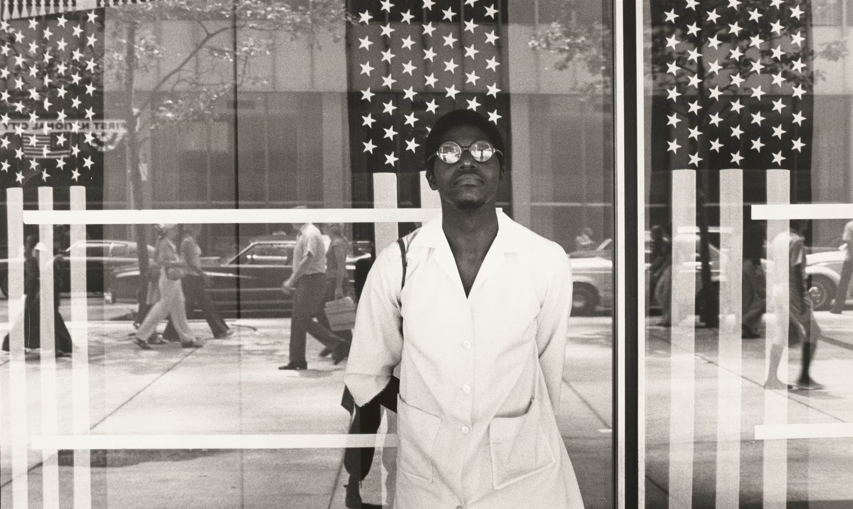

America seen through Stars and Stripes, New York City, New York, 1976, by Ming Smith. Photograph: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts/Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Astounding shots of a wounded civil war major and a flogged Black man sit amid amateur snaps and propaganda in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum – showcasing the nation’s unrivalled mastery of the camera.

As the land of the free and the home of the brave reverberates to cries of Make America Great Again, what is often overlooked is the complicated notion of the word “again”. As highlighted in American Photography, an expansive, sometimes beautiful but often shocking survey at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam over the past two centuries, what has been great for some has been downright awful for others.

“America and photography are entwined. You can’t see the two apart from each other,” says Mattie Boom, curator of photographs at the Rijksmuseum, who has spent two decades helping build the American collection. It now amounts to around 7,000 photographs – all by American photographers of American subjects – and 1,500 American photobooks and magazines. The current exhibition is the first major survey of the field to be staged in Europe, and is a triumphant swansong for Boom as she retires from her post.

There is no hierarchy to the selection. A sequence of rooms present numerous fields – portraiture, landscape, advertising work, art photography – like chapters in a novel. “We tried to find surprising images and things we’ve never seen before,” says Boom. The result is a broad mix, shaped with co-curator Hans Rooseboom, of anonymous photography, commercial work, news coverage, medical prints and propaganda, presented in tandem with masterpieces such as Robert Frank’s enigmatic picture of a woman watching a New Jersey parade in 1955, her face partially obscured by an unfurled Stars and Stripes.

Photography proved to be the perfect medium for the new world: fast, largely democratic in its availability (if not its dissemination) and cheap. At the Rijksmuseum, two 19th-century daguerreotypes hint at the fractures to come. The first is one of the oldest known American photographs: a tiny 1840 self-portrait of Henry Fitz Jr, a pioneer photographer from Long Island. He captures himself with his eyes closed. Another plate, taken seven years later in the studio of Thomas M Easterly, an accomplished daguerreotypist in St Louis, pictures Chief Keokuk – also known as Watchful Fox – leader of the Sac and Fox people. It humanises the Native American chief – his face is astoundingly sharp – while also viewing him as a novelty.

Signs of racism – and its opposition – ripple through the galleries, as images of segregation and plantations give way to documentary photographs of the civil rights movement. A carte de visite studio portrait taken in the 1860s shows a semi-naked Black man scarred from multiple floggings, a horrible picture used to positive ends in a campaign for the abolition of slavery. Nearly a century later, in 1957, Jack Jenkins pictured Black student Elizabeth Eckford arriving at the newly integrated Little Rock Central High School to a jeering mob of white women. The photograph’s power lies in Eckford’s extraordinary composure in the face of such hatred.

The epic grandeur of the American landscape is largely absent from the walls – with the exception of a majestic albumen print of Cathedral Rocks, Yosemite, taken by Carleton E Watkins in 1861. Instead photographs show the conquest of nature and its bounty: Margaret Bourke-White’s widescreen shots of wheat plains; postcards of oil wells in Oklahoma. Meanwhile, in the monochrome street photography of Saul Leiter and William Klein, we discover the ragged beauty of American cities, both its bustling sidewalks and lonesome figures, its cinemas and storefronts.

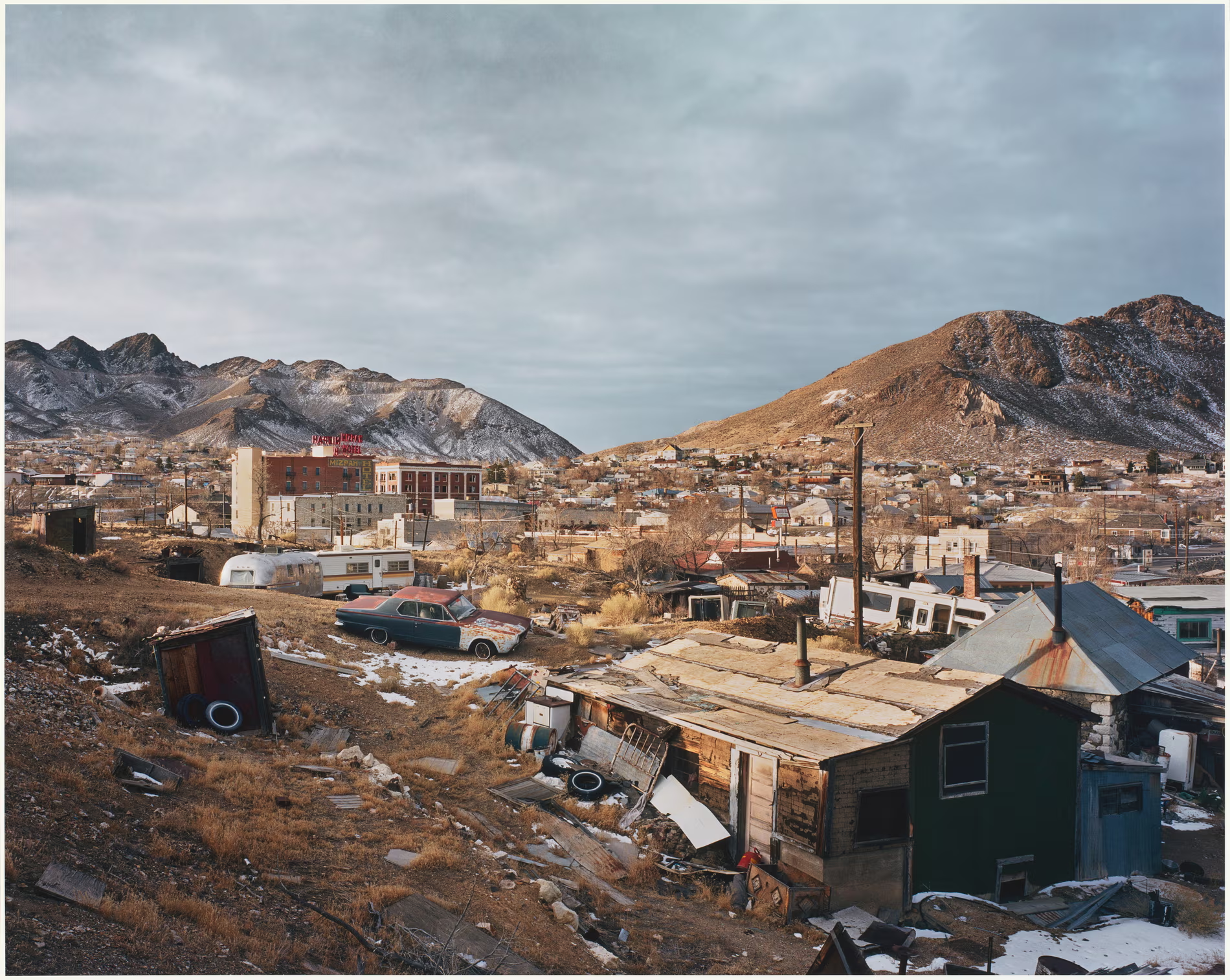

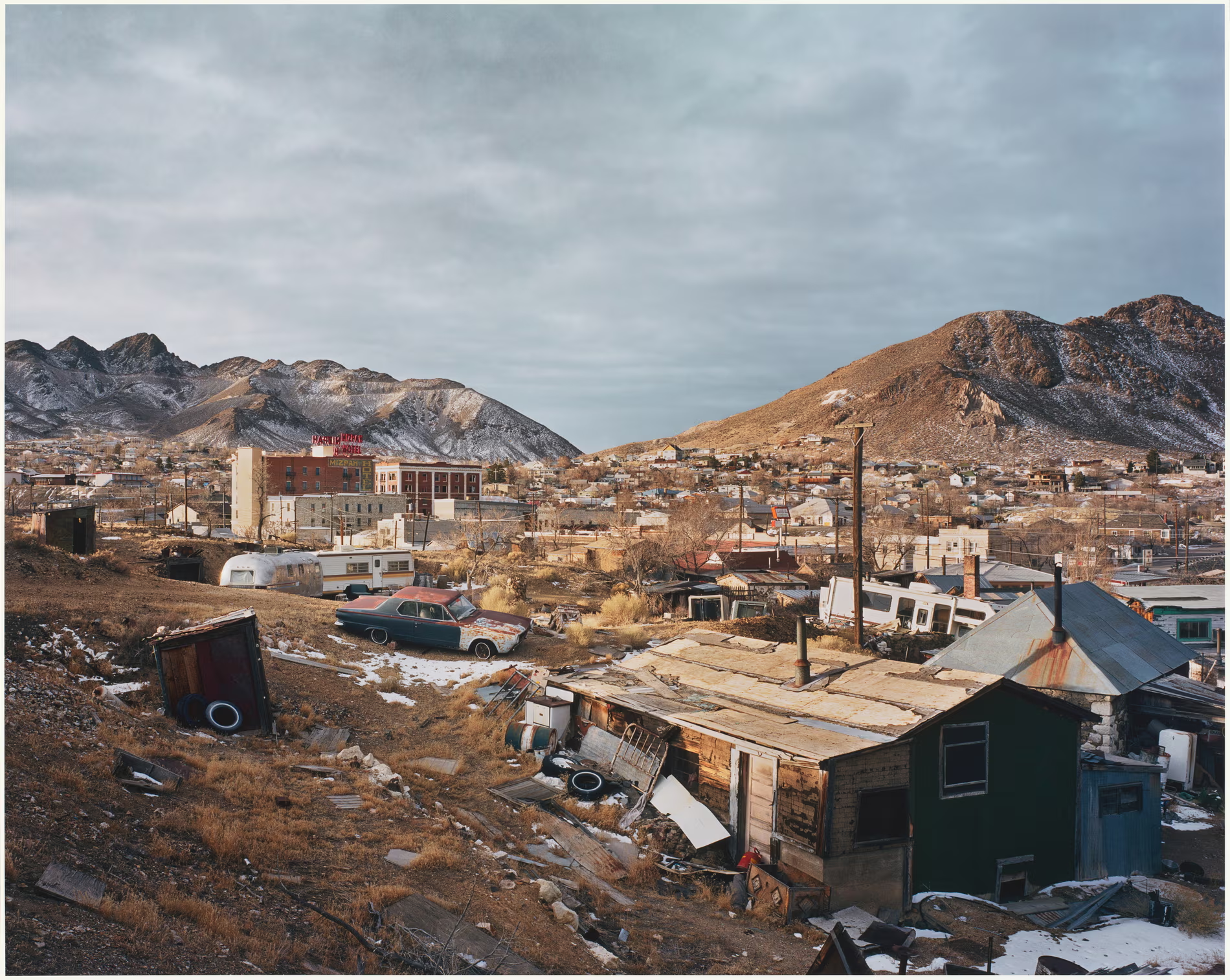

Ragged beauty: Tonopah, Nevada, 2012, by Bryan Schutmaat. Photograph: Rijksmuseum Henni van Beek/Bryan Schutmaat

And, naturally, American photography sold stuff – Tupperware, confectionery, toboggans, razor blades, station wagons and, of course, Coca-Cola – in peppy, sometimes surreal, advertising campaigns. One early example at the Rijksmuseum is a small late-19th-century photo-card promoting a Manhattan butcher, in which a moustachioed merchant stabs his tenderloin cuts alongside some out-of-control alliterative copy: “Finest Flesh, Fattest Fowl, Freshest Fish, Furnished.”

During the 1930s, many avant garde photographers fled Europe for the US, energising the medium in their adoptive nation. An aerial view of tire tracks in a snowy Chicago car park, taken by Hungarian émigré László Moholy-Nagy in 1937, is indicative of these fresh perspectives. And photographers with an edge became highly sought after in postwar America, as full-throttle capitalism accelerated its development. Companies tried ever more eye-catching ways to attract customers and the gaudy palette of shop windows and flickering neon can be found reflected in the colour-saturated covers of Playboy and Time.

Perhaps the strongest sell was to keep America American. During the second world war, photographic posters, featuring the all-American eagle in flight, called on patriots to enlist in the civil defence. Another used Walker Evans’s photographs of small-town life to extol the virtues of a nation “where, through free enterprise, a free people have carved a great nation out of a wilderness. This is your America.” The your was conditional.

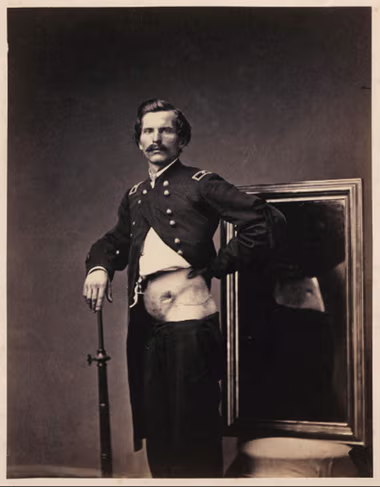

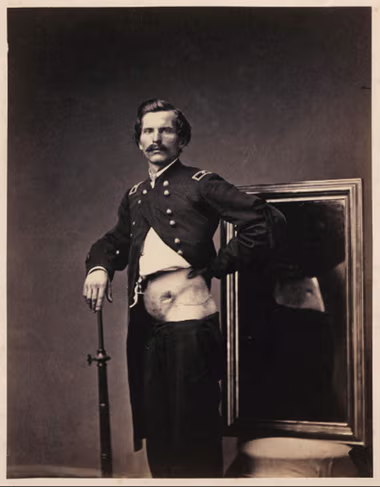

Ghosts of conflict … Major H A Barnum, Recovery after a Penetrating Gunshot Wound of the Abdomen with Perforation of the Left Ilium. Photograph: Smithsonian American Art Museum

The ghosts of conflict also materialise in two poignant portraits: an 1865 study of a civil war major, with a colossal bullet wound through his abdomen but still standing tall in his uniform; the other, a record of the 2006 wedding day of a badly injured Gulf war soldier.

The Rijksmuseum presents some eccentric mini-collections within its American holdings. A mixed group of photographs – each annotated with the word “Me” to indicate where the various owners are situated in the frame – was one of several boxes donated to the Rijksmuseum by a New York collector of amateur snapshots. “He has sorted them out by category,” Boom says. “There’s a box called ‘Views from the car’. ‘Ladies by televisions’ is another category. He has a whole wall of these boxes in a little room and he gives donations to museums.”

But the most mysterious pictures on view are a pair of monumental cyanotypes of human torsos, discovered in the mid-1990s at the 26th Street flea market in Manhattan, objects with a shady past worthy of a true-crime podcast. These 1930s positives were printed from X-ray negatives of cross-sectioned frozen cadavers as part of a university study in Chicago. Recent research has uncovered that the subjects were largely Black Chicagoans – who endured a death rate twice that of their white neighbours – and that the bodies were used in an institution that didn’t accept Black medical students. The exhibition illustrates photography’s power both to illuminate and obfuscate.

On the road … Homegirls, San Francisco, 2008, by Amanda López. Photograph: Jaclyn Nash/Jaclyn Nash, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Boom equates 20th-century American photography with Dutch golden age painting. Both, she points out, were created “for citizens, by citizens and bought by people all over.” But is this a particularly European edit of an imperfect American dream? Boom shrugs. It would, she acknowledges, probably be more reverent if it were staged in the US, where celebratory monographic shows dominate. “For them the big names – Edward Weston, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Richard Avedon – they are part of the history of the country, they are part of the image culture of the country, and for them these names are the same as Rembrandt and Vermeer for us Dutch.”

In its subjective way – a different selection would tell a different story – the exhibition looks at American life in the round, with trauma and contradictions adjacent to glamour and enterprise. “It’s full of the force of photography, so it doesn’t leave things out,” says Boom. “America has always been 10 years ahead of Europe with photography and it still is.” It is one area in which – incontrovertibly and tellingly – America has always been great.

American Photography is at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, until June 9th.

This blog post was adapted by Catherine Couturier Gallery from an orginal article in The Guardian by Christian House.

American Photography: Unforgettable Images of the Beauty and Brutality of a Nation

Posted on Feb 14, 2025

America seen through Stars and Stripes, New York City, New York, 1976, by Ming Smith. Photograph: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts/Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund

Astounding shots of a wounded civil war major and a flogged Black man sit amid amateur snaps and propaganda in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum – showcasing the nation’s unrivalled mastery of the camera.

As the land of the free and the home of the brave reverberates to cries of Make America Great Again, what is often overlooked is the complicated notion of the word “again”. As highlighted in American Photography, an expansive, sometimes beautiful but often shocking survey at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam over the past two centuries, what has been great for some has been downright awful for others.

“America and photography are entwined. You can’t see the two apart from each other,” says Mattie Boom, curator of photographs at the Rijksmuseum, who has spent two decades helping build the American collection. It now amounts to around 7,000 photographs – all by American photographers of American subjects – and 1,500 American photobooks and magazines. The current exhibition is the first major survey of the field to be staged in Europe, and is a triumphant swansong for Boom as she retires from her post.

There is no hierarchy to the selection. A sequence of rooms present numerous fields – portraiture, landscape, advertising work, art photography – like chapters in a novel. “We tried to find surprising images and things we’ve never seen before,” says Boom. The result is a broad mix, shaped with co-curator Hans Rooseboom, of anonymous photography, commercial work, news coverage, medical prints and propaganda, presented in tandem with masterpieces such as Robert Frank’s enigmatic picture of a woman watching a New Jersey parade in 1955, her face partially obscured by an unfurled Stars and Stripes.

Photography proved to be the perfect medium for the new world: fast, largely democratic in its availability (if not its dissemination) and cheap. At the Rijksmuseum, two 19th-century daguerreotypes hint at the fractures to come. The first is one of the oldest known American photographs: a tiny 1840 self-portrait of Henry Fitz Jr, a pioneer photographer from Long Island. He captures himself with his eyes closed. Another plate, taken seven years later in the studio of Thomas M Easterly, an accomplished daguerreotypist in St Louis, pictures Chief Keokuk – also known as Watchful Fox – leader of the Sac and Fox people. It humanises the Native American chief – his face is astoundingly sharp – while also viewing him as a novelty.

Signs of racism – and its opposition – ripple through the galleries, as images of segregation and plantations give way to documentary photographs of the civil rights movement. A carte de visite studio portrait taken in the 1860s shows a semi-naked Black man scarred from multiple floggings, a horrible picture used to positive ends in a campaign for the abolition of slavery. Nearly a century later, in 1957, Jack Jenkins pictured Black student Elizabeth Eckford arriving at the newly integrated Little Rock Central High School to a jeering mob of white women. The photograph’s power lies in Eckford’s extraordinary composure in the face of such hatred.

The epic grandeur of the American landscape is largely absent from the walls – with the exception of a majestic albumen print of Cathedral Rocks, Yosemite, taken by Carleton E Watkins in 1861. Instead photographs show the conquest of nature and its bounty: Margaret Bourke-White’s widescreen shots of wheat plains; postcards of oil wells in Oklahoma. Meanwhile, in the monochrome street photography of Saul Leiter and William Klein, we discover the ragged beauty of American cities, both its bustling sidewalks and lonesome figures, its cinemas and storefronts.

Ragged beauty: Tonopah, Nevada, 2012, by Bryan Schutmaat. Photograph: Rijksmuseum Henni van Beek/Bryan Schutmaat

And, naturally, American photography sold stuff – Tupperware, confectionery, toboggans, razor blades, station wagons and, of course, Coca-Cola – in peppy, sometimes surreal, advertising campaigns. One early example at the Rijksmuseum is a small late-19th-century photo-card promoting a Manhattan butcher, in which a moustachioed merchant stabs his tenderloin cuts alongside some out-of-control alliterative copy: “Finest Flesh, Fattest Fowl, Freshest Fish, Furnished.”

During the 1930s, many avant garde photographers fled Europe for the US, energising the medium in their adoptive nation. An aerial view of tire tracks in a snowy Chicago car park, taken by Hungarian émigré László Moholy-Nagy in 1937, is indicative of these fresh perspectives. And photographers with an edge became highly sought after in postwar America, as full-throttle capitalism accelerated its development. Companies tried ever more eye-catching ways to attract customers and the gaudy palette of shop windows and flickering neon can be found reflected in the colour-saturated covers of Playboy and Time.

Perhaps the strongest sell was to keep America American. During the second world war, photographic posters, featuring the all-American eagle in flight, called on patriots to enlist in the civil defence. Another used Walker Evans’s photographs of small-town life to extol the virtues of a nation “where, through free enterprise, a free people have carved a great nation out of a wilderness. This is your America.” The your was conditional.

Ghosts of conflict … Major H A Barnum, Recovery after a Penetrating Gunshot Wound of the Abdomen with Perforation of the Left Ilium. Photograph: Smithsonian American Art Museum

The ghosts of conflict also materialise in two poignant portraits: an 1865 study of a civil war major, with a colossal bullet wound through his abdomen but still standing tall in his uniform; the other, a record of the 2006 wedding day of a badly injured Gulf war soldier.

The Rijksmuseum presents some eccentric mini-collections within its American holdings. A mixed group of photographs – each annotated with the word “Me” to indicate where the various owners are situated in the frame – was one of several boxes donated to the Rijksmuseum by a New York collector of amateur snapshots. “He has sorted them out by category,” Boom says. “There’s a box called ‘Views from the car’. ‘Ladies by televisions’ is another category. He has a whole wall of these boxes in a little room and he gives donations to museums.”

But the most mysterious pictures on view are a pair of monumental cyanotypes of human torsos, discovered in the mid-1990s at the 26th Street flea market in Manhattan, objects with a shady past worthy of a true-crime podcast. These 1930s positives were printed from X-ray negatives of cross-sectioned frozen cadavers as part of a university study in Chicago. Recent research has uncovered that the subjects were largely Black Chicagoans – who endured a death rate twice that of their white neighbours – and that the bodies were used in an institution that didn’t accept Black medical students. The exhibition illustrates photography’s power both to illuminate and obfuscate.

On the road … Homegirls, San Francisco, 2008, by Amanda López. Photograph: Jaclyn Nash/Jaclyn Nash, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Boom equates 20th-century American photography with Dutch golden age painting. Both, she points out, were created “for citizens, by citizens and bought by people all over.” But is this a particularly European edit of an imperfect American dream? Boom shrugs. It would, she acknowledges, probably be more reverent if it were staged in the US, where celebratory monographic shows dominate. “For them the big names – Edward Weston, Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Richard Avedon – they are part of the history of the country, they are part of the image culture of the country, and for them these names are the same as Rembrandt and Vermeer for us Dutch.”

In its subjective way – a different selection would tell a different story – the exhibition looks at American life in the round, with trauma and contradictions adjacent to glamour and enterprise. “It’s full of the force of photography, so it doesn’t leave things out,” says Boom. “America has always been 10 years ahead of Europe with photography and it still is.” It is one area in which – incontrovertibly and tellingly – America has always been great.

American Photography is at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, until June 9th.

This blog post was adapted by Catherine Couturier Gallery from an orginal article in The Guardian by Christian House.

Comments (0)

Add a Comment